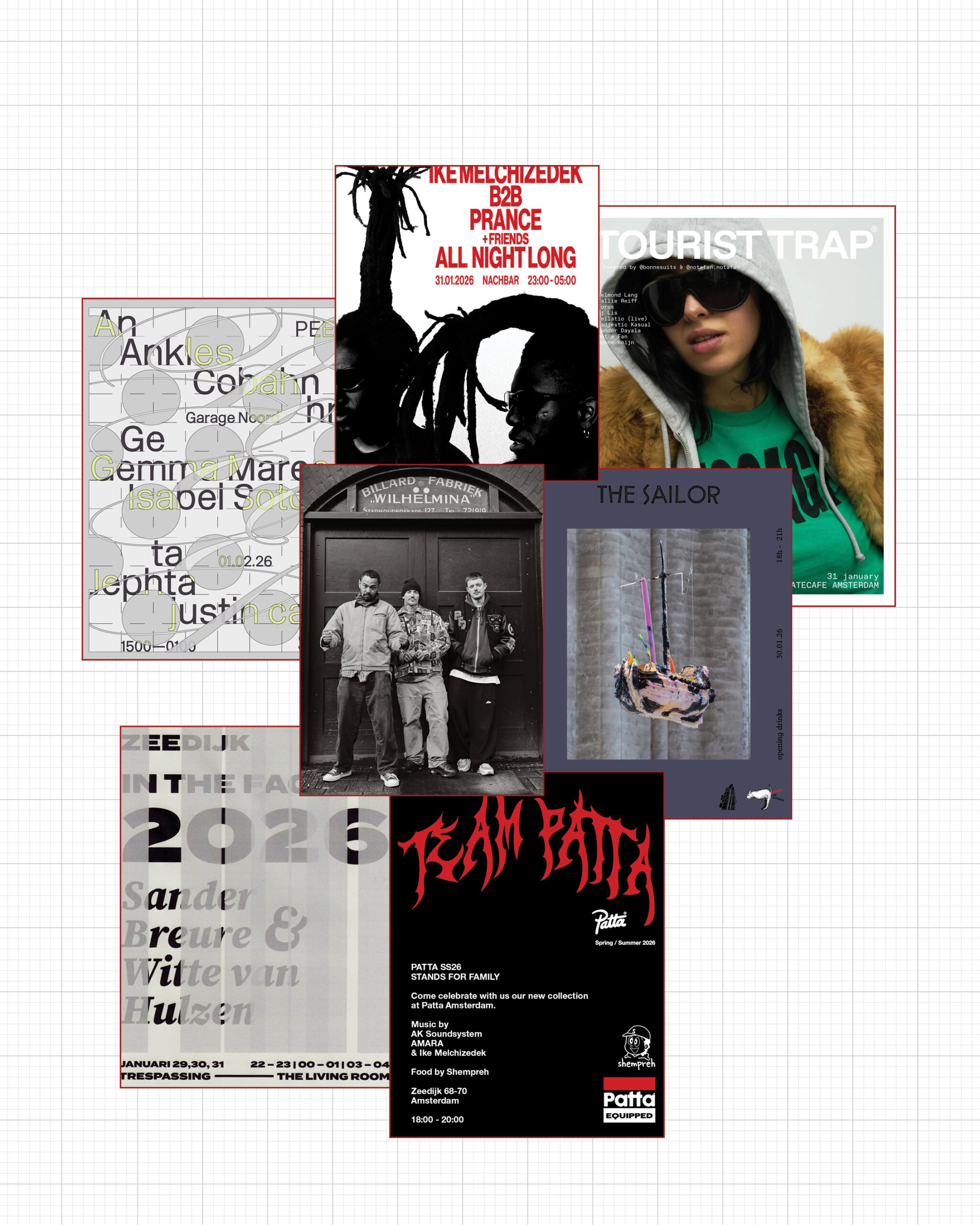

“To keep vigil is to assert the precarity of existence in the face of loss” writes curator Isabella Greenwood, and perhaps there’s no better distillation of Vigil: Death and the Afterlife.

Co-curated by Greenwood and Doron Beuns and brought together by Thomus Dacosta’s Shipton Gallery and Pim Lamme’s Semester 9, Vigil is an immersive contemplation of mortality. It feels less like a straightforward narrative and more like an emotional and psychological journey. One that lingers long after you leave. It’s raw, weirdly tender, and achingly cool – like stumbling into a funeral where everyone is dressed in Rick Owens, the air thick with grief and incense, but no one is crying.

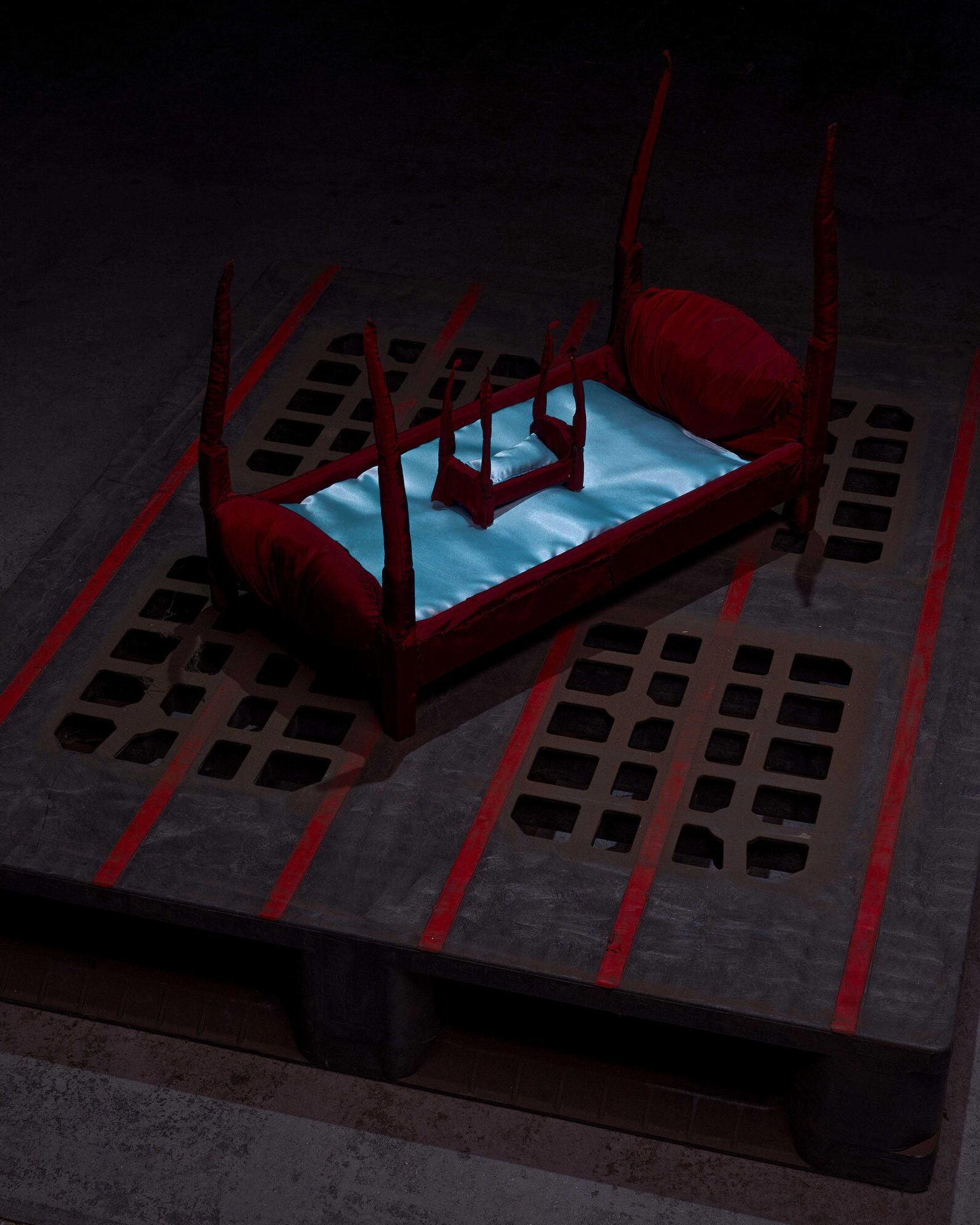

Set in the industrial abyss of Loods 6, Vigil gathers 25 contemporary artists, each interrogating death’s aesthetics, politics, and existential absurdity in our age of turmoil. The sprawling former warehouse feels like a purgatorial holding zone, with dim corridors and glowing installations that beckon you toward something intangible. This isn’t an exhibition; it’s an experience. You walk through decay, liminality, and post-human speculation as if trying to find your own little slice of the afterlife.

Greenwood’s curation begins with the mortality of the body, grounding visitors in the physicality of death and the immediacy of loss. The opening chapter, Towards the Afterlife, feels visceral and raw.

Ella Fleck’s When You Wish Upon a Star is a striking presence within this section, its humanoid figure hidden beneath crumpled sheets, a phone glowing eerily. Its familiarity is unnerving; the sterile light of technology highlights our detachment in modern life, always pulling us away from true human experience. One thought lingered for me with this work: doomscrolling is a form of death.

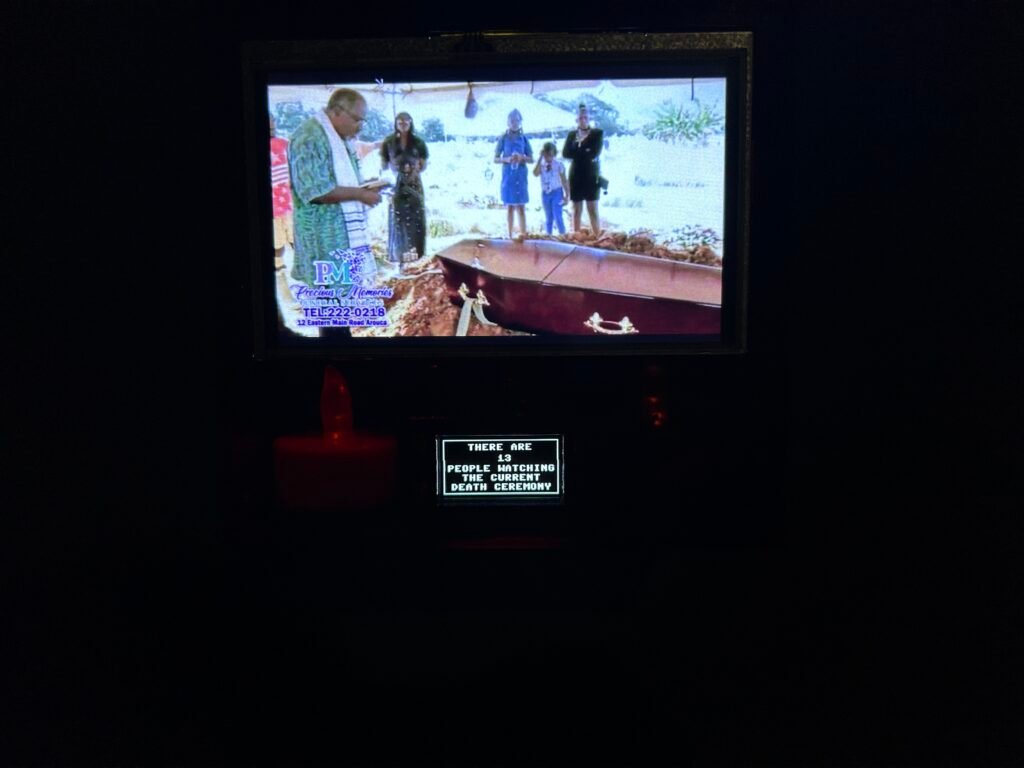

While Fleck’s work reflects humanity’s penchant for voyeurism, Max Otis King’s Votive Watching makes anyone who approaches it a voyeur. By appropriating obscure funeral live streams, King heartbreakingly highlights the lonely yet collective ways we grieve in an age of technology. It’s a stark reminder that even in the algorithmic void, our rituals persist. These opening works immerse viewers in the undeniable and unembellished reality of death.

Then things get weird.

The middle section, The Liminal Realm, feels like slipping into a fever dream, where the body begins to dissolve. Anna-Lena Krause’s ghostly sculptures, which suggest bodies shedding their physical form, integrate seamlessly. Her figures hover between worlds, their translucence quietly provoking thoughts about presence and absence, mortality and memory, and the tension between what remains and what fades away.

What’s striking here is the refusal to make sense of liminality. Instead of neat narratives about heaven, hell, or purgatory, the works evoke disintegration, uncertainty, and the thrill of transformation. Here, death isn’t a destination. It’s a detour, a waiting room, a glitch in the simulation.

By the time you reach Beyond the Afterlife, you’re fully untethered. This final section is pure speculation, imagining post-human futures where death as we know it becomes obsolete. Simon Chovan’s hive-like cocoons, crafted from volcanic soil and synthetic textures, feel alive and alien, like relics from a world where humans are no longer the main event. Melle Nieling’s door installation, featuring a video of a protagonist confronting a kind of virtual demise, is underscored by AI-generated Latin hymns that echo through the dark space. It’s both unsettling and strangely comforting, blurring the line between sacred tradition and technological alienation.

The genius of Vigil lies in its refusal to preach or resolve. It doesn’t spoon-feed meaning but invites you to wrestle with your own mortality. As Achille Mbembe notes in Necropolitics, Western culture has sanitized death, hiding it in hospitals, algorithms, and neatly packaged narratives. This exhibition drags it back into the open. Not as a tragedy, but as a transformation, a disruption of the “normal” that defines life itself.

Go, not to “understand” but to inhabit the discomfort. Death is here, it’s always been here, and in Vigil, it finally feels like it’s ours again.