What is Henna?

Henna: A natural dye derived from the leaves of the Lawsonia inermis plant. Traditionally used for temporary body art and hair coloring, henna holds cultural significance across Southeast Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African cultures.

Origins

- A Migratory Practice: The henna plant and its application have traveled across regions for over 5,000 years, with a continuous presence in Southeast Asia, Egypt, and the Middle East.

- Unclear Beginnings: While the exact origin remains debated, some trace early representations of henna to 4th-century depictions of Bodhisattvas, enlightened figures, in Ancient India.

- Ancient Egypt’s Connection: One of the earliest recorded uses dates back to around 3400 BCE in Egypt, where henna was applied to the nails and hair of mummified pharaohs. It symbolized purity, spiritual protection, and status, and was believed to preserve and strengthen the skin in the afterlife.

Henna as medicine

While often associated with body art, henna has long held medicinal significance across cultures — symbolically linked to cycles of life and death, protection, and healing. Traditionally, it was used to treat skin ailments, reduce pain, and cool the body, though internal use is now rare.

- One of the earliest references appears in the Ebers Papyrus, a foundational Egyptian medical text, where henna is noted for treating skin conditions and regulating body temperature in the desert heat.

- In traditional Chinese medicine, henna has been used to reduce fever, inflammation, and muscle aches. In West African healing practices, henna leaves are applied as soft wraps to support wound healing and reduce swelling.

- In some Middle Eastern and North African traditions, small doses of henna were ingested to ease internal discomforts and gastrointestinal issues.

- Across South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, henna remains a key element in hair care — valued for its natural conditioning, dyeing properties, and soothing effect on the scalp.

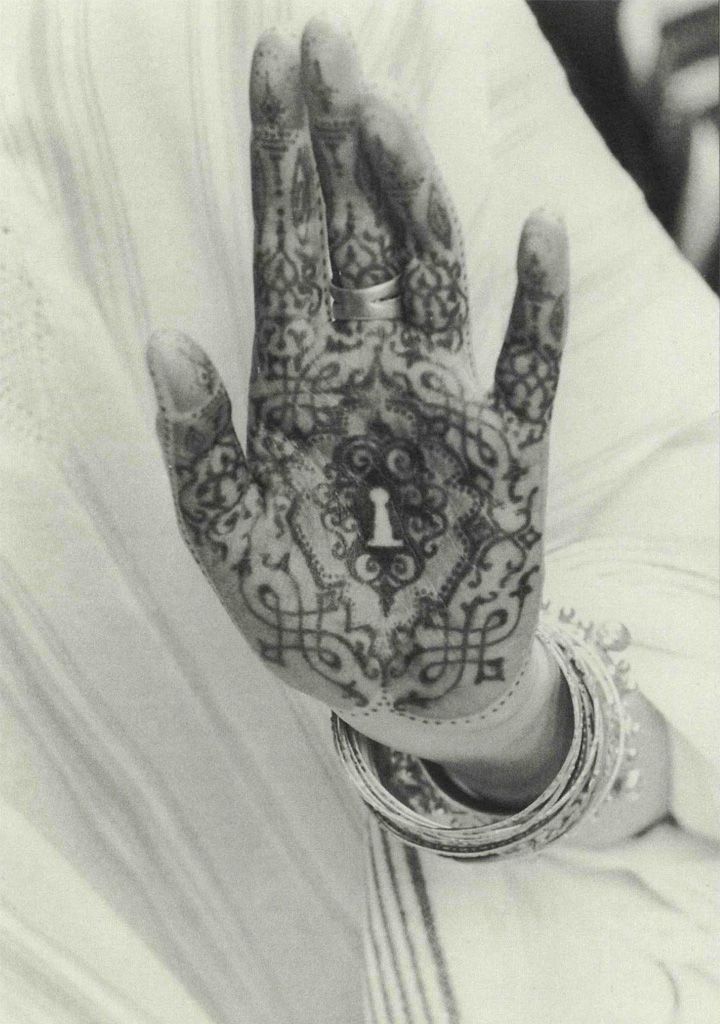

Henna in Body Art – Cultural Significance

Henna’s role in body art is layered — both protective and celebratory. Across the regions where it’s used, it functions as a symbol of beauty, ritual, and spiritual safeguarding.

- India: Known as mehndi in Hindi and Urdu, henna is deeply tied to blessings, love, prosperity, and major life events. It’s a key part of weddings and festivals, where the depth of the stain is often seen as a sign of good luck and strong relationships.

- Middle East & North Africa: Henna has historically been used not only for adornment but as a ritual act – believed to purify, protect, and celebrate. It’s worn during rites of passage, holidays, and moments of transformation, often linked to beauty and spiritual defense.

- Henna & the Evil Eye: In South Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African cultures, henna is part of broader protection rituals against the evil eye — a force associated with envy and misfortune. Here, henna is more than decoration. It becomes a talisman, used to repel negativity, attract good fortune, and protect the wearer.

Night of Henna

- Henna is widely used as a rite of passage — most notably in pre-wedding ceremonies across North African, Middle Eastern, and South Asian cultures. Each region has its own version of the Henna Night: a ritual gathering where the bride’s hands and feet are adorned with intricate designs. Often an intimate, women-only event, it’s a space for collective celebration, storytelling, and quiet blessings — a moment to mark transition, reflect, and prepare for the next chapter.

Henna Postpartum

- Beyond weddings, henna also plays a role in postpartum care. In many cultures, applying henna to a new mother’s feet is believed to offer protection from malevolent spirits, ease emotional distress, and aid in recovery. It becomes part of a sacred pause — encouraging rest, connection, and healing.

- These traditions are more than symbolic. They reflect henna’s deeper purpose as both ritual and remedy — a physical and emotional support system that reinforces community care during life’s most vulnerable thresholds.

Henna as Expression and Resistance

In recent years, henna has become a medium for personal expression, cultural reclamation, and quiet resistance across different communities.

Traditionally practiced by women, henna rituals have often excluded men. But in South Asian queer and non-binary circles, the practice is being reclaimed as a space for self-definition and fluidity. Applying henna becomes both a personal and political gesture — a way to rewrite tradition on one’s own terms.

In Wānās, Henna, and the City, anthropologist Gehad Abaza documents how Sudanese refugee women in Cairo use henna to survive and stay connected to home. She shares the story of Narwal, who fled war and now turns her childhood craft into a livelihood. For women like her, henna is more than ornament — it’s a form of continuity, resilience, and resistance in the face of displacement, racism, and marginalization.

Moroccan photographer Lalla Essaydi also reclaims henna in her visual work. By layering Arabic calligraphy — historically reserved for men — onto women’s bodies, fabrics, and spaces using henna, she subverts expectations around gender, authorship, and cultural visibility.

Across borders and identities, henna continues to shift. What was once a private ritual becomes a public statement.

Our bodies as Living Archives

Sociologist Andrew Blaikie writes about the body as a living archive. A site where memories, identities, and social histories are inscribed. Through this lens, henna becomes a tool that turns the body into a memory museum.

A hand painted with henna is more than decoration. It becomes a surface for storytelling, carrying personal milestones, cultural values, and collective traditions. Like markings on a cave wall, each design holds meaning, each stain a quiet reminder of something passed down or lived through.

In 2024, UNESCO recognized henna as an intangible cultural heritage, acknowledging its role in preserving memory across generations and geographies.