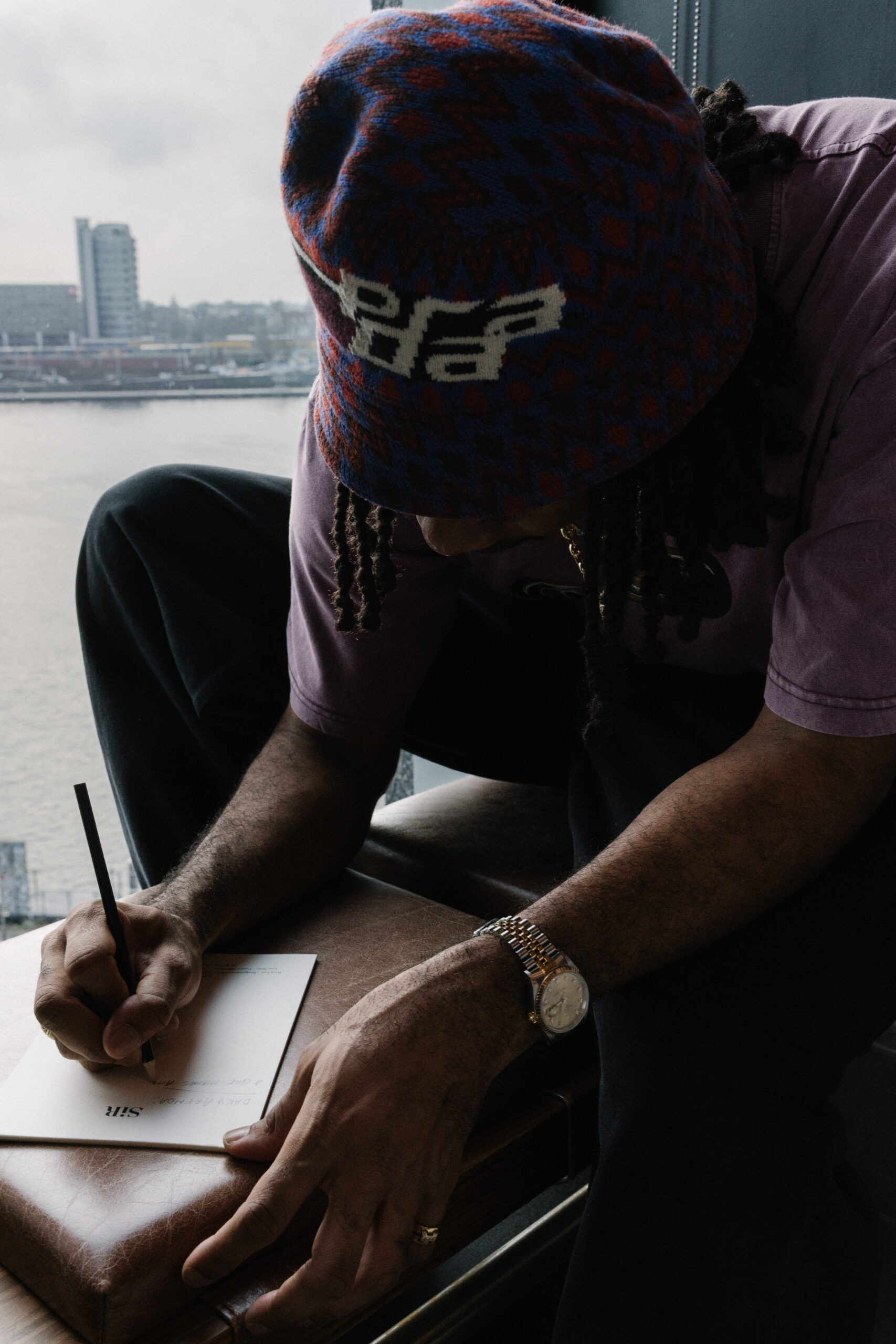

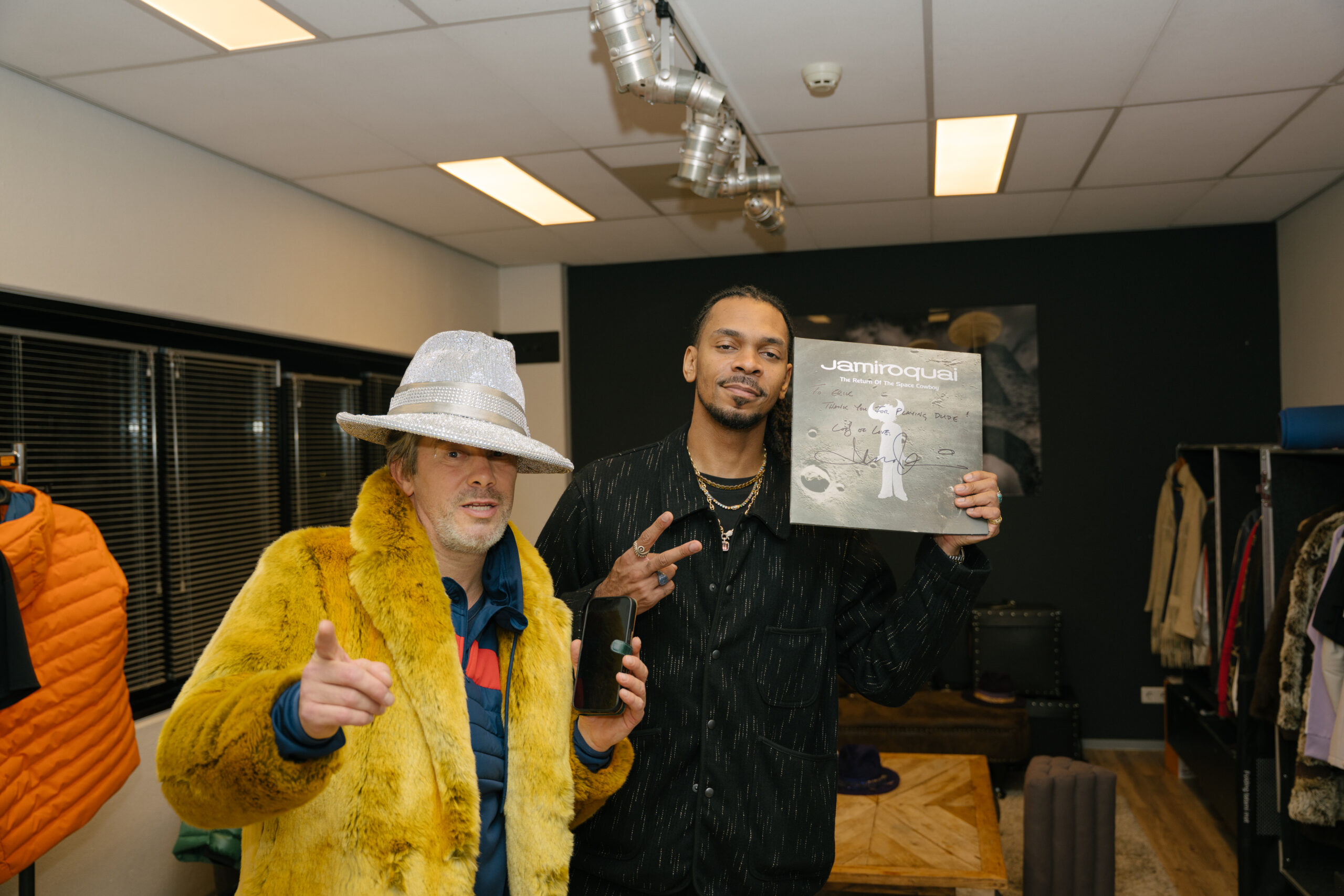

With Jamiroquai set to take the Ziggo Dome stage in an hour and 17.000 people already halfway to another planet, Erick the Architect is in the booth doing surgery on the room. He is the one building the pressure before the funk lands, sliding between classics and deep cuts, sneaking in songs with 200 plays next to songs with 90 million, testing how open a crowd really is.

A few days later we are at Bacalar in Amsterdam Noord, heads still ringing, sharing tuna tostadas. We order our usual spicy margarita, he goes for a mezcal negroni. Between bites and sips we move from Matrix lore to New York paranoia, from Afrobeats in Paris to gospel in Brooklyn living rooms.

If you know Erick, you probably met him first as one third of Flatbush Zombies, the Brooklyn group that turned psychedelic New York rap into a full universe and made him its main in-house producer.

Now he’s entering a different chapter. There’s his debut solo album I’ve Never Been Here Before, released in February 2024, a project that slips between hip hop, soul, dub, psych, and something harder to name, with a deluxe director’s cut stretching the story even further. There’s the breakout feature on Jungle’s Candle Flame, and a new album on the horizon for next year. His collaborative catalogue reads like a cross-section of modern music: A$AP Rocky, Tech N9ne, James Blake, Joey Bada$$ and more.

Before all that, Erick was shaping worlds visually as much as sonically: a trained graphic designer whose eye for mood, texture and narrative still threads through everything he makes.

Somewhere between the mezcal and the last bite, we press record.

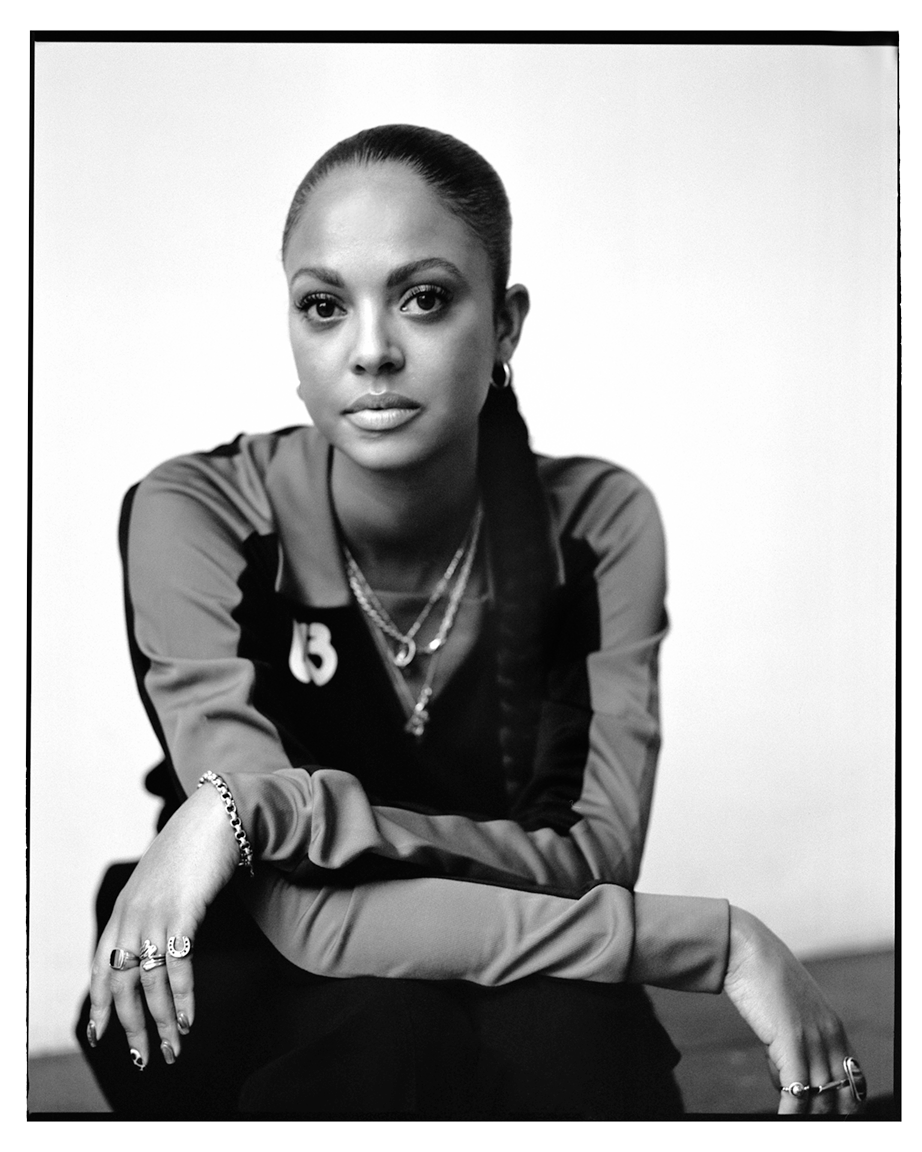

Interview by Anastasia Gviniachvili & Awa Anne

Awa: Your artist name is Erick the Architect. How did that come about?

Erick: My favorite movie is The Matrix. In the hood you get a nickname, right, but I never really had one.

There is this character in the movie, the Architect, the guy in the white room with all the screens, watching every version of reality at once. People focus on Neo, Trinity, Morpheus. I was always drawn to the Architect. He is the mastermind in the background.

I grew up thinking architecture was only buildings and structures. But music is architecture too. A producer is a blueprint. You have to trust a blueprint before you invest money and time into a building. It is the same with songs. The arrangement, the skeleton, the bones. So I took the Architect from the movie and made it about sound. I build worlds instead of houses.

Awa: When you create, do you lead with method or intuition, or does the architecture of a song reveal itself later?

Erick: It is both. If I am making music for myself, there is a comfort. I know my own temperature. I might start by sampling a record or just sitting at the piano. Those are my home base.

With other people I am more methodical. I always start with a conversation. I do not think any great piece of music ever started with “play some beats bro”. It is always that talk you have before you make anything.

The conversation becomes a journal for what we are about to make. Most of the time that talk is the catalyst. Even when it is just about the records we grew up on, who our moms were playing in the house. You pull those memories into the present.

I really believe you are never the first person to make something. Some ancestors are helping. Whether you believe that or not.

As long as you are being yourself and not compromising, that is success. You can be mainstream and still be you. You can be underground and still be corny. None of those labels matter.

Anastasia: Was “the Architect” your role in Flatbush Zombies from early on?

Erick: In Flatbush Zombies that became my job without us ever saying it out loud. Meech and Juice brought the energy and the attitude, and I was the one stitching the whole world together sonically.

Awa: How did Flatbush Zombies come together in the first place?

Erick: Me and Meech grew up on the same block. Juice and Meech met in school. We were just kids smoking, joking, hanging out, making weird music in my house without imagining anyone would hear it.

Anastasia: Do you feel like you were seen as underground or mainstream, and what do you think about that divide?

Erick: People look at us like we are some underground group but we were doing shit that so many mainstream artists never got to do. We did late night TV without even having an album out. We played Coachella. We toured the world. That whole underground versus mainstream thing is kind of fake to me.

There is barely a middle class in music anymore. You are either everywhere or nobody knows who the hell you are.

For me it is simple. As long as you are being yourself and not compromising, that is success. You can be mainstream and still be you. You can be underground and still be corny. None of those labels matter.

To understand Erick, you have to go back to where it started: Flatbush, Brooklyn. Once a Dutch settlement, later shaped by waves of Caribbean migration, Flatbush grew into one of New York City’s most culturally layered neighbourhoods: a place where Jamaican, Trinidadian, Haitian, and Latino communities reshaped the streets through food, language, and music.

It wasn’t just the backdrop to his childhood; it was the foundation: the early imprint of rhythm, culture, and community that would later echo through his work.

Anastasia: Does New York influence how you make music?

Erick: Hell yeah. New York is my whole operating system.

I grew up in Brooklyn, but my kindergarten class already looked like the United Nations. Jamaican, Haitian, Polish, Slavic, kids from everywhere, and we were all in the same room. Later on you jump on the train for $1.50 and in 1 hour you have a completely different world. Harlem, the Bronx, Washington Heights, Yonkers. Each stop has its own sound.

California is not like that. It is more segregated. People would ask me how I even met my Mexican homies because they could not imagine those worlds touching. In New York, that is normal.

Anastasia: How did New York carve your sense of awareness or self protection?

Erick: If you are from New York you are a little paranoid by default. When I first moved to California, people would say “How are you doing” and I would answer “What do you want”. Back home, small talk usually comes with a request.

People call that trauma, and some of it is. But there is also an awareness that comes from growing up like that. For years my walk to school included the thought “Am I going to get robbed today”. As wild as that sounds, it builds a tolerance and a sense of alertness. Those values get baked into your personality. They can work for you or against you, but they are there.

I am still a star, but one part of me is bent, chipped, human.

Awa: What is one piece of advice for anyone trying to move through the world less scared?

Erick: Keep your imagination alive and do not confuse that with being naive.

The older we get, the more jaded we become. We stop playing games, stop being curious, stop letting ourselves be fans of anything. I still love video games and toys.

Imagination is how you fight fear. If you believe there is still something new to learn, you are not as intimidated when the world changes. You do not feel like a new thing is here to erase you.

At some point our table at Bacalar turns into an informal music history seminar. Paris comes up, then Afrobeats, then the 3 rules of sampling.

Erick: Around 12 years ago my friends from West Africa started bringing me to these crazy parties in Paris. They were playing Davido, Mr Eazi, all this stuff that felt completely new to me at the time. They would fill stadiums with these artists. Back then Afrobeats felt like a secret. Now it is everywhere.

As a producer my first instinct when I hear someone like Fela Kuti is to sample him. Not for money, but from pure inspiration. I cannot play horns like that, so maybe I borrow something and flip it. For me there is an art to sampling.

Awa: Do you have rules for your sampling process?

My rules are simple:

One, you listen to the whole record before you chop anything. If I am taking from your work, I owe you 40 minutes of my attention at least.

Two, I do not like just looping and dropping drums. I grew up obsessed with people like Pete Rock, J Dilla, DJ Premier, Alchemist. They rearranged music, cut it into pieces and built a new structure. Most of the time I want you to almost not recognize where I got the sample from.

Three, I do not sample something that came out last summer. If it is that new, why are you sampling it already? Sampling, to me, is about what our moms played, what was in the house, the weird song you found in a bargain bin. Not “this went viral on TikTok last year, let me loop it”.

Anastasia: What makes you a good DJ?

Erick: Taste. You cannot be a DJ without taste.

I am going to play something you know and something you do not know. I am not playing the unknown record to flex. I am trying to put you on, the same way your friends send you songs they swear you will love.

A good set, to me, is when you pull out Shazam at least once. There should be a moment where you think “What is this” and a moment where you go “Damn I forgot about that song”. If you could have stayed home and let a streaming algorithm play the exact same thing, that is not DJing.

Anastasia: And how is it to be the opening act on the Jamiroquai tour? Or an opening act in general?

Erick: I’ve only opened for people whose music I admire. I can’t imagine being put in a situation where I’m opening for somebody who’s not that great to me but the opportunity is too big to pass on. So my relationship with it is very healthy.

Being an opener is only weird because I’m a main character too. So you kind of have put your ego aside and realise you’re not the most important thing tonight. You know, humble yourself and step into a space where people can discover you, but also realise that you’re not the biggest thing here and create a platform for the other person to go after it to capitalize on your energy. And also know that part of his success or their success is due to you too…

Anastasia: Opener or main act – what’s your overall experience with touring? I can imagine it must be very different to discover new cities while touring compared to being a tourist.

Erick: I’ve been on tour for the past like 13 years of my life – a big contrast from the start of my life, as I never traveled anywhere, never left New York ever. Back then we wrote these songs about escaping and wanting to see what the world was like. So I think that there’s a certain humility attached to people who are from where I’m from because you wish and you wonder and you watch all these other people experience that and you’re like, well, what are the steps I have to follow in order to make that my reality too? So when you actually do it, to me, I swear to God, put us on everything. I forget that I’m going to get paid every fucking time. I don’t think about it.

On the other hand, touring is expensive and it’s time consuming. People say that I’m so lucky. And I definitely am, but don’t make it seem like what I’m doing is not sacrificial. You have to sacrifice something in order to achieve your goals. So as much as it’s great, you miss out on birthdays, you miss out on shit that’s important, too.

Erick released his debut solo album I’ve Never Been Here Before in 2024, a 16-track odyssey that threads fearlessness, black resilience, beauty in darkness, and a sense of togetherness into a soundtrack that slips between hip hop, soul, dub, psych, and everything that lives in the in-between. Made largely in his Los Angeles home studio, the record gathers both longtime collaborators and new voices: Joey Bada$$, James Blake, Westside Boogie, George Clinton, Channel Tres, Kimbra, Lalah Hathaway, Pale Jay, RÜDE CÅT and more, each adding their own frequency to a project that feels expansive yet unmistakably personal.

Awa: Your album is called I Have Never Been Here Before, and the symbol attached to it is this imperfect pink star you designed. Why did that title and that image feel like the right way to mark this chapter?

Erick: I wanted a symbol that even a child could recognize. Think about the McDonalds M, you know what it is long before you understand every meaning behind it.

I’m a graphic designer myself and for the album I designed a pink star. A real geometric star has perfect symmetry. I made one arm imperfect on purpose. That is me. I am still a star, but one part of me is bent, chipped, human.

The title is about that feeling. On paper I have been releasing music for years, touring the world, doing features. But this is the first time I made a project that spoke fully for myself. Emotionally I had never been in this place before. Confidence wise, spiritually, all of it. The music is just the evidence.

When we talk about stand out tracks he does not mention the obvious singles. Instead he goes straight to a slow burner.

Erick: “Breaking Point” is probably the best thing I have ever made. It is also the hardest song I have ever had to finish.

The beat originally belonged to someone else. We wrote over it, then I found out it had been given to a legendary artist. I could have let it go, but the writing felt too honest. Baby Rose and Rueben James had already put pieces of their soul into it.

So I called my friend Jacob, Pale Jay, and asked him to rebuild the whole thing from scratch. He played everything live and sent it back from another country, and suddenly we had a new skeleton that still carried the same emotion.

By the time I recorded my verse, the song felt like a room full of people processing their own heartbreak. When I heard the final mix I cried. Not because it was sad, but because it proved a song can hold you the way someone else’s music held you when you were younger.

There’s a certain humility attached to people who are from where I’m from because you wish and you wonder and you watch all these other people experience that and you’re like, well, what are the steps I have to follow in order to make that my reality too?

Anastasia: You mention you’re a graphic designer, has your work as a designer influenced how you make music, especially when working on this album?

Erick: Hell yeah – they’re one and the same. Sometimes I’ll think about the way that I want to be perceived before I even make the music. In today’s time, the aesthetic of something is so impressionable: People don’t even know what something is, but they know what it looks like. It’s an advantage to be able to have that come from the same person. For somebody that has to outsource it to another person they have to trauma dump, emotionally dump, whatever it is in their mind and then the designer has to figure out how to put that into visuals. Whereas, I can go to the library, call my best friend, and pull all these ideas together, and then put my phone on do not disturb and I just make it.

Anastasia: How is the process of designing different from making music?

Erick: Design was something that I was taught in university so I approach it in a formal way. But with music, I had no training in music, so it’s very intuitive. And I really feel like that’s a blessing.

Awa: So how did you get to music? How did you unlock that for yourself?

Erick: My mom was blind, so music became the way we communicated because she couldn’t see me mature. If music was the only thing that really brought my mom peace, I wanted to be the person who could do that… to light up somebody’s feelings like that.

I would go to the blind community quite often, and I realised how important music was because sometimes that’s all they had. So I decided I wanted to make music. And not only hip hop, I wanted to make jazz, electronic music, everything, because the people in that community, in my neighborhood, and in my family were like a whole diaspora of different genres.

I didn’t know how to formally make music, so it felt like a puzzle I had to figure out. I always had a dream of being a superhero, and when I started making music, it really made me feel like one.

Anastasia: Can you single out an artist or song you heard as a kid who changed the way you saw music?

Erick: Probably Marvin Gaye. I would say What’s Happening Brother? Then I’d say my favorite vocalist of all time is Donnie Hathaway and my favorite artist ever is James Brown.

Anastasia: Talking about great music, when do you know that a track is done? Where do you draw the line and make the decision that it’s ready?

Erick: [Laughing] When your manager tells you to upload it on the internet. The label’s like, yo, what’s up? That’s when you do it. Otherwise, I would be like D’Angelo. I’d have one song in like, 10 years. Because once you release the music, it’s no longer yours, it’s the world’s.

Awa: You just opened a new chapter with the album, with the tour, with this whole solo chapter. What’s next?

Erick: I feel like the next album I am working on is going to change my life.

The first one was ambitious on purpose. It had to introduce people properly, especially those who only knew me as “the guy from Flatbush Zombies”. The next one is sharper. Easier to listen to but more powerful for me.

I am pulling from everywhere. Gorillaz, Depeche Mode, System of a Down, the stuff that was actually playing in my house growing up, not just what people expect from a New York rapper.

Anastasia: Where do you see yourself in 5 years? In 10 years?

In 5 years I want to be in my own superhero era. Helping younger artists, using my platform to spotlight their work, being one of the few real people left in a world full of artificial noise.

In 10 years I see myself as a family man, still making things, but with a foundation under my feet that lets me move because I want to, not because I have to.

For now, I am just following where the blueprint leads.